“I can’t feel the panel.” This is how I summarised my first day at the EASST/4S conference taking place in “virPrague” to my partner. Put frankly, I felt a bit frustrated. I had been looking forward to the conference for quite a long time, excited that it would offer me multiple chances: the chance to share findings from my research in a panel on inequality I had set up together with my colleague Nelius Boshoff from Stellenbosch University, whom I was really looking forward to meet again in Prague; the chance to present myself to the STS community, which I am trying to connect with and make myself belong to. Being a post-doc whose affiliation provides a highly interesting space to carry out science studies, yet is not linked with STS institution-wise, I am tasked to build up my scholarly network somewhat on my own – and the EASST/4S conference promised to be a great opportunity to progress in this regard. As much as I was curious about the research presented at the conference, I was curious about getting to know people personally – and, admittedly, as an academic with care responsibilities, I was also curious about having some days abroad, just for myself, even if it was for work.

These were my expectations, before COVID-19 changed life substantially. When the organisers announced the conference would not be cancelled but shift into virtual space, I was happy and relieved that the efforts of application had not been in vain, yet also wondering which of my initial expectations would materialise, as ‘face-to-face’ interaction would be mediated by technology.

‘Locating and timing matters’, also for virtual conferencing

Now the conference started like this for me: I was waiting for my mum to arrive to look after the children, so that I could eventually finalise my presentation scheduled for day two, while I had also selected ten panels (for day one only) which I deemed highly relevant and thought I shouldn’t miss. The first sessions, then, felt rather odd. I was sitting at my desk at home, with an unstable internet connection, trying to follow talks while hearing my children play outside. This was when I first realised how ‘locating and timing’ mattered – also with regard to participating in a virtual conference. My timing had been bad due to the delay in preparing my talk. And my location made it rather difficult to concentrate.

I found it somewhat hard to switch my mind into a conference mood, and suddenly realised how much it makes a difference to physically ‘be’ somewhere. The presentations I listened to were most interesting; however, I couldn’t ‘feel’ the panel. Over the course of the conference, the informal rule and habit emerged that listeners switched off videos and mics during the talks, and only turned them on for asking a question or making a comment afterwards. This was for good reasons, including to save privacy and bandwidth. However, I perceived a downside to this practice, namely that the reaction of the audience during the talks could hardly been grasped. One could not see facial expressions, hear murmurs or laughter in the room, see people taking notes or sending bodily signs that show their intention to engage in interaction. I realised that active listening is obviously only one of various bodily actions which usually take place when I am in a room with a speaker in front. What it also does at a subconscious level is absorbing the ambiance and the audience – and this is what I was missing.

Physical presence matters for discursive exchange

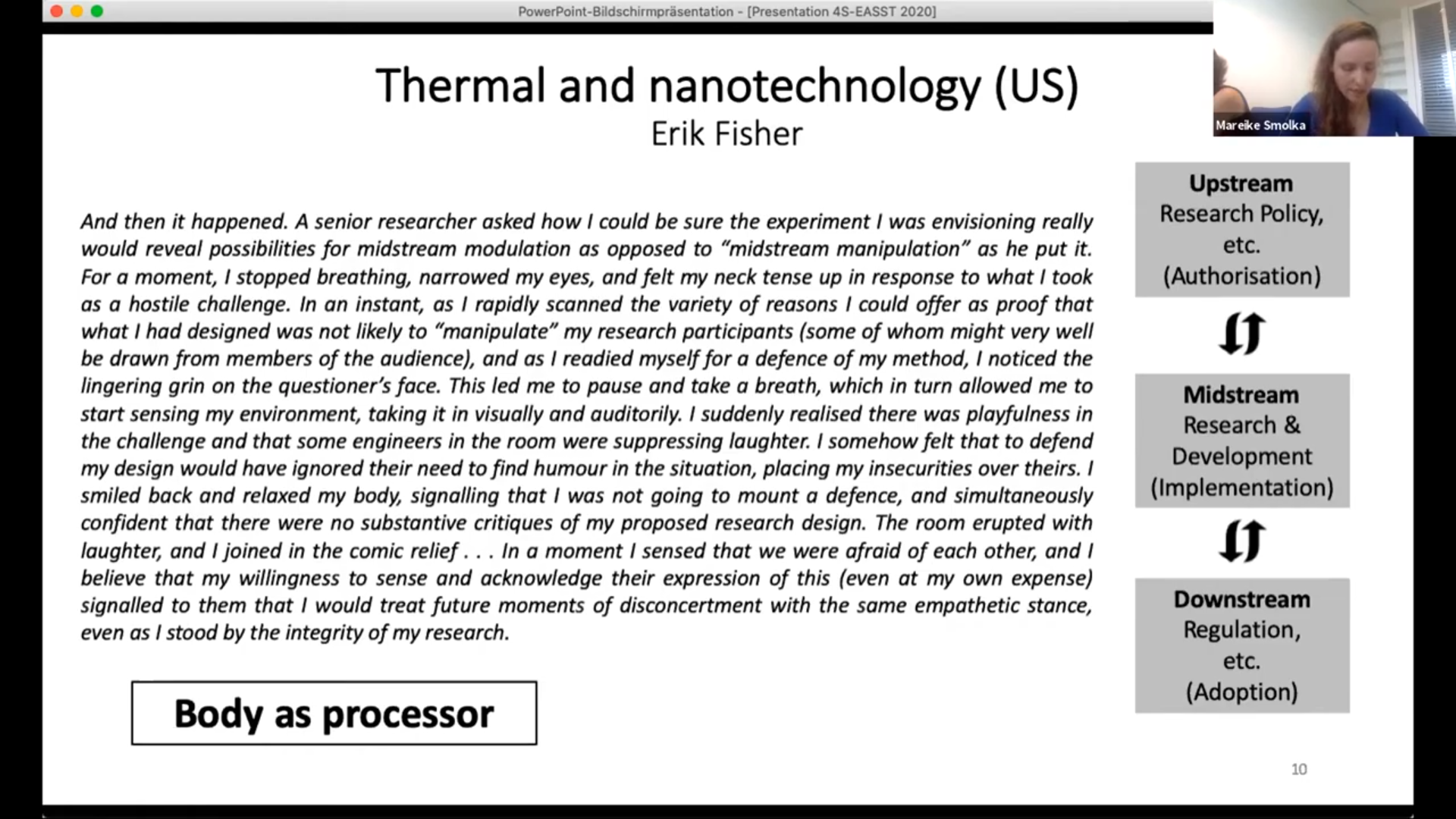

How much such bodily perceptions matter for the scientific discourse, albeit in a different context, was broached by a panel organised by Mareike Smolka, Ricky Janssen and Cristian Ghergu from Maastricht University, which dealt with “Affects, emotions, and feelings in data, analysis, and narrative”. In the first of two sessions, Mareike Smolka presented insights from on-going research on the relation between affect and collaborative action in interdisciplinary collaborations carried out together with Erik Fisher (Arizona State University) and Alexandra Hausstein (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology).1 They highlighted how tensions that emerge in interdisciplinary collaborations are as much cognitive as they are bodily felt by providing auto-ethnographic experiences such as the situation when Erik Fisher was challenged by a senior member of a research group he was meant to collaborate with in the context of Socio-Technical Integration Research. The text passage they used for illustration is captured by the screen shot below:

While I was listening to Mareike reading out this passage loudly, I thought: Yes, this is exactly what is lacking in the virtual conference space – the ability to “detect” and “process” the affective dimension of colleagues’ reactions (these are the terms used by Mareike, Erik, and Alexandra), to feel how their comments resonate with my own questions, assumptions, and interests. In a virtual space where you only see one or two faces on a screen surrounded by black squares with white letters, it is hard to feel the affective dimension of our research – “to move with and be moved by” (Mareike, Erik, and Alexandra citing Myers, 2012: 177) other bodies and their curiosities.2

The absence of physical presence complicates the conference situation not only for speakers, but also for listeners, particularly first-time participants who would benefit from experiencing how peers in a scientific community react to each other. This is difficult to grasp on a screen where people appear only to ask the speaker their question. And it also makes it more challenging for ‘newcomers’ to get into the conversation. Not being physically together in a room made it considerably more challenging to sense when the right moment has come to raise my hand (i.e., to click on the blue hand in Zoom), ask a question or make a comment (which in the realm of scientific conferences is also a performative act with image-building effects; see Hitzler and Hornbostel, 2014: 71). Some moments of awkward silence following the end of talks made me think I may not be the only person insecure in this regard.

Feeling virtual vibes, finally

What I described so far, however, is not the full picture of my conference experience. During the first two conference days, I somewhat struggled with the lack of immediacy sitting alone in my room while listening to scholars’ presentation. But then on Thursday something unexpected happened: I started to feel conference vibes. It happened while I participated in the panel on affects, emotions and feelings, and in hindsight, I think it happened not only due to the inspiring talks and lively debates starting off in the panel, but also as its topic made me reflect about my own affects as conference attendant. This reflection helped me to reconcile the fact that I was bodily at home, which also meant my kids would sometimes come for a cuddle or climb on my knees, but that I was somewhere else mentally at the same time. On Friday, when I attended the last sessions, the virtual vibes of the conference even made me write some enthusiastic and personal tweets (which I usually refrain from posting):

All in all, and with a bit of time having passed, I see that the EASST/4S conference in its virtual format has actually met a lot of my initial expectations. Although I did not encounter scholars face-to-face, I was able to connect with colleagues and continue exchange via emails, which partly offered more substantial exchange than small talks at a coffee break. This is not to say that I would not have loved to have a coffee break in Prague. However, in hindsight, I see more and more the advantages this virtual format has offered – such as being able to bring my kids to bed after the conference days were over, and to watch recorded sessions I was unable to attend simultaneously. Eventually, the conference made me aware of the fact that I am able to feel virtual vibes, which was truly a new experience to me.

1 Their conference paper was titled “From Affect to Action: Choices in Attending to Disconcertment in Interdisciplinary Collaborations”.

2 I want to thank Mareike Smolka, Erik Fisher and Alexandra Hausstein for granting me permission to incorporate the screen shot including the vignette, as well as for clarifying concepts and making instructive comments on an earlier version of this text.

Bibliography

Hitzler R and Hornbostel S (2014) Wissenschaftliche Tagungen – zwischen Disput und Event. In: Behnke C, Lengersdorf D and Scholz S (eds) Wissen – Methode – Geschlecht: Erfassen des fraglos Gegebenen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 67–78.

Myers N (2012) Rendering Life Molecular: Models, Modelers, and Excitable Matter. Durham: Duke University Press.