Limn is a scholarly magazine that focuses on contemporary problems arising at the intersection of politics, expertise and collective life. It is also an experiment in scholarly production in the interpretive human sciences that explores new kinds of collective work and publication. Limn is available both in an open access web format and in print. Each issue of the print magazine has a custom graphic design, with a range of imagery and graphic material related to the contributions.

We created Limn in response to a set of concerns that arose from our shared background in the rapidly changing field of American cultural anthropology during the 1990s and 2000s. At the time, the discipline encouraged individualized work on particular sites or multi-sites, and valorized virtuosic interpretation and writing, while leaving little space for collaborative inquiry or concept work beyond abstract discussions of “theory.” However appropriate these orientations were for anthropology as traditionally conceived, a different approach seemed to be required for studying some of the topics that were moving to the center of the discipline at the time, such as science, technology, bureaucratic rationality, and planning. Given this background—and against it—we were all interested in exploring how research on specific sites or multi-sites might be brought into communication, and what alternative models of inquiry, writing, and publication might foster collaboration.

Initially, we pursued these questions, both together and separately, through well-established vehicles of collective work, such as conference panels, workshops, collected volumes, and joint projects. Our first experiment with novel directions in collective work was the Anthropology of the Contemporary Research Collaboratory (ARC), a collaboration with Paul Rabinow. ARC was a setting in which we began to think about models of inquiry that would allow researchers working on disparate sites to explore common problems that had contemporary significance. In launching Limn as separate initiative, we were particularly concerned question such as: How to expand the network of collaborators? How to establish a distinctive approach to the anthropology of the contemporary while remaining open to cross-fertilization with other approaches? How to re-imagine what scholarly work and publication can be after the Internet and open access? And how might collaboration provide a fresh way to respond in a timely manner to contemporary problems?

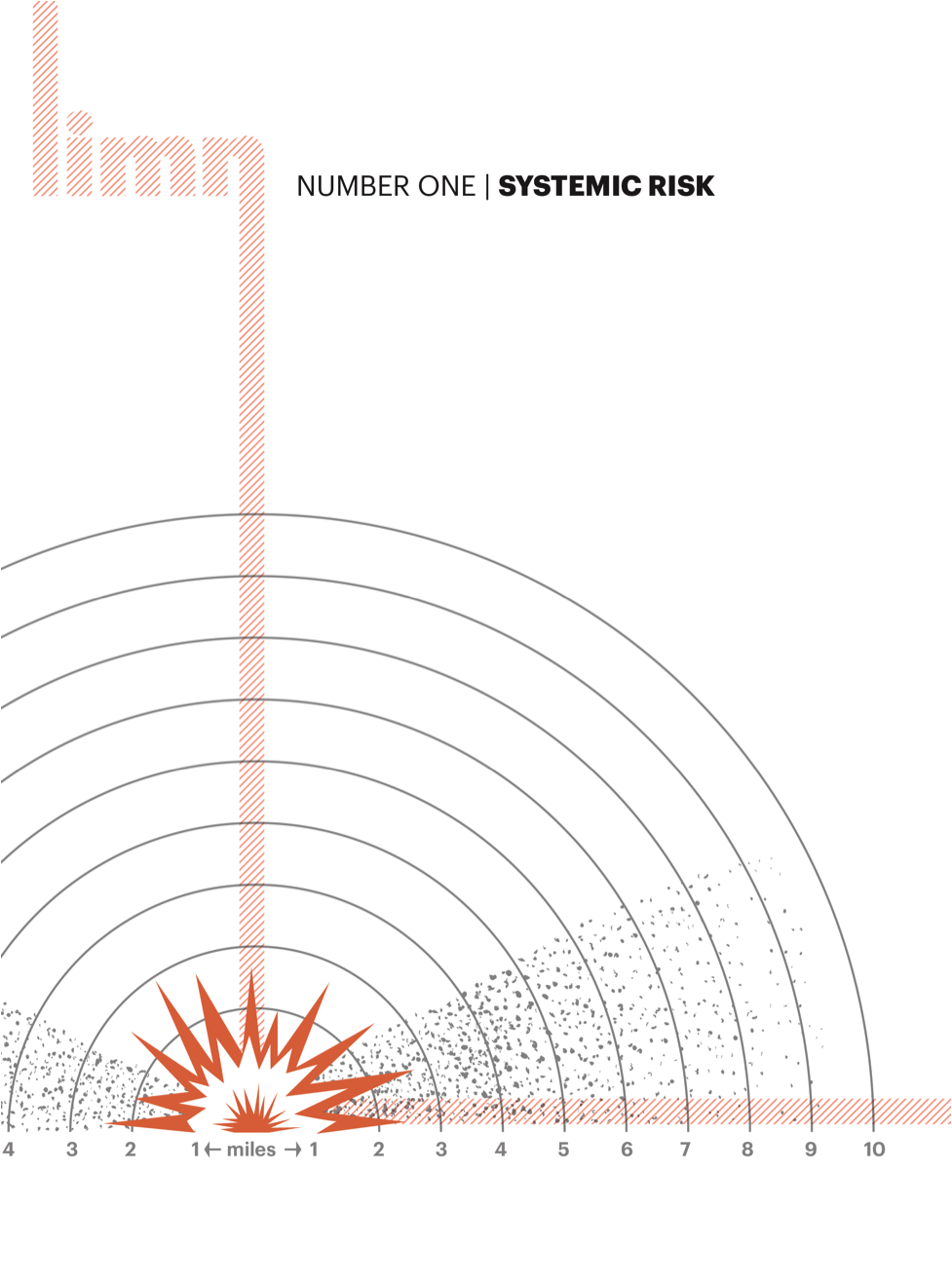

The 2009 Deepwater Horizon disaster provided a push in thinking about these issues. In various problem-domains—from computer security, to pandemic preparedness, emergency management, and critical infrastructure protection—we had all been thinking about the renewed contemporary concern among experts and policymakers with the vulnerability of critical systems and had been in communication with colleagues working along parallel lines. We initially entertained the idea of asking some of these colleagues to comment directly on the Deepwater Horizon event. Eventually, however, we settled on a different approach: to shed light on the event by placing it in the context of other events, sites, and problem-areas that raised similar questions, and that pointed to genealogical framings that might help understand why it was being taken up, and responded to, in a particular way. This, initially, was what we meant by “Limn”: to illuminate the space around the event, to understand how it became intelligible, thinkable, and governable. Limn 1, the issue that eventually emerged out of these discussions, was centered on the problem of “systemic risk,” as well as the norms, such as resilience and preparedness, that are invoked in response.

In the course of work on Limn 1 we took note of a productive dynamic. Although we had started with a sense of a core problem that would shape the issue, the process of identifying a group of contributors, discussing possible contributions, and ultimately reading and commenting on those contributions broadened our frame of reference. In this case, it allowed us to think about how a concept from a particular domain—systemic risk was specifically a term of art in financial regulation—might illuminate a broader problematization of contemporary life. Many of our subsequent issues have settled on a term from a particular field that seems to illuminate a broader set of problems: disease ecology, public infrastructure, chokepoints, and hacks, for example. In other cases, we have adapted such “first order” terms to designate something pervasive but as yet unnamed: such as “little development devices,” the “total archive,” or “sentinel devices.”

This orientation to shaping shared problems has given rise to a distinctive work process. In considering proposals for issues, we undertake an intensive and sometimes laborious process—involving both the general editors and the “issue editors” who have made the proposal—of identifying the core concept or problems that should be at the center of the issue, and the historical framing that will bring it to life. A great deal of this work takes place in the crafting, revising, and narrowing of prompts which we use to identify and then invite particular people to participate in an issue. These prompts are not published, and the work that goes into them is not directly visible in the journal itself, though they often provide a first outline for the introduction or preface to each issue.

This orientation to shaping shared problems has given rise to a distinctive work process. In considering proposals for issues, we undertake an intensive and sometimes laborious process—involving both the general editors and the “issue editors” who have made the proposal—of identifying the core concept or problems that should be at the center of the issue, and the historical framing that will bring it to life. A great deal of this work takes place in the crafting, revising, and narrowing of prompts which we use to identify and then invite particular people to participate in an issue. These prompts are not published, and the work that goes into them is not directly visible in the journal itself, though they often provide a first outline for the introduction or preface to each issue.

Limn has also been an experiment in scholarly publishing in a time of rapid and significant change in that world. Limn has built on various experiences: Kelty’s experience with the success of the blog Savage Minds, the collaboration around ARC, the rise and spread of open access, and the rapid change in the availability and suitability of technical tools suitable for both online publication and DIY print publication. Limn is also a reaction to the standardization and normalization of journals and article forms, to the disciplinary gate-keeping that often governs academic publishing, and the slow publication process and public inaccessibility of most disciplinary journals. Despite what might have been an obvious (and labor-saving) choice to go all-digital, we also recognized early on that the print magazine still commands a large degree of respect and authority among academics, and confers a sense that the endeavor is more than a blog or a kind of online confab. Our commitment to producing a bespoke design for each issue is both a tribute to the history of the small magazine (and a desire to preserve that form and practice in the face of digital dissolution), and an attempt to think about design, juxtaposition, layout, format as elements of a collaborative enterprise.

All the work on Limn is done by the three general editors (Collier, Kelty, and Lakoff), the graphic designer (Høyem), copyeditors and research assistants, and, crucially, the co-editors who work on, and have generally proposed, a particular issue. Thus far we have been lucky to have such input from Lilly Irani, Nick Seaver, Frederic Keck, Mikko Jauho, David Schleifer, Bart Penders, Xaq Frohlich, Boris Jardine, Antina von Schnitzler, James Christopher Mizes, Biella Coleman, Peter Redfield, Jason Cons, Townsend Middleton, Ashley Carse, and Alice Street. The bulk of the money we spend goes to the design of the print version. Thus far, there has been no marketing or promotion, and no involvement from any professional press or journal, and no managing editor; all production and distribution for the journal relies on other infrastructures (tools like Amazon’s CreateSpace or MailChimp), which are both liberating and at the same time, unstable.

Since the first issue of Limn in 2011, this labor-of-love, small-scale, outsider experiment has exceeded our expectations. As of this writing, we are about to release our tenth issue. We have published over fifteen hundred pages of writing by more than one hundred twenty contributors. Over one thousand subscribers are on our mailing list and our twitter account has more than one thousand followers. Anecdotally, our colleagues appreciate Limn as a welcome alternative to existing venues of scholarly publishing. Despite the fact that Limn offers none of the professional rewards of publication in standard academic journals, nearly all of the authors we invite to write for Limn agree to do so.

We reflect frequently on the kind of future we imagine for Limn—and whether, indeed, it should have a future, or should be concluded as a limited experiment that has run its course. What remains at the heart of the endeavor and keeps us engaged is the desire to find a form for collaborative inquiry that escapes the more stultifying aspects of normal university and disciplinary life, and that sustains and valorizes intellectual engagement. We continue to discuss Limn as if it were more than a magazine—as an umbrella, network, or platform—and frequently ask ourselves how the model might evolve. Are there ways in which a “Limn 2.0” might better realize those ambitions by opening up the editorial collective, or loosening our own sense of what this platform is good for? Might there be opportunities to explore collaboration with an established press? Or would the compromises (to accessibility, to format, to the genre of contribution) outweigh the benefits of greater support in editing, production, and distribution?