How to be part of innovations is one of the crucial questions of many academics. This text deals with a question of innovation as a process of re-thinking and re-doing already existing ideas, mainly the academic findings and their consequences on non-academic world. While many academics do admit that our subjects of study are inevitably part of the research processes, the next step should be to innovate the relations outside the academia, especially after the research is done.

For many years now, STS has focused on how different socio-technical matters and worlds are enacted and for whom. In many ways, those questions are turning back to STS scholars themselves. For whom are STS theories and objects of knowledge enacted? One of the questions opened at the plenary Meeting Machines was a question of „applied STS“; similar questions were raised in the panel on multidisciplinarity (what is interdisciplinarity in practice?) and methodography (what is co-laboration in practice?). Connecting these three questions might be useful while thinking about STS and innovations.

Innovation is not necessarily about producing something new, but it also can be about re-thinking and re-making something already existing. According to Craig Calhoun, innovation is mostly “not only coming up with a new idea but continuously improving existing ideas” (Calhoun 2009). To improve existing ideas, it is necessary to co-laborate with those we study, i.e. to mutually involve ourselves with the object of study (e.g. Niewöhner 2016). Co-laborations are nothing new but often rather hidden or silenced. I suggest to keep re-thinking innovations and co-laborations; not only to give voice to those we study, but also focus on our (academic) role in the processes of innovations. Re-thinking the mode of engaging with the object of study can make us be part of, or influence, the socio-technical innovations being studied. Thus, one of the crucial questions of innovations within (social) sciences should be how to co-laborate and engage with our “subjects of study” more and better.

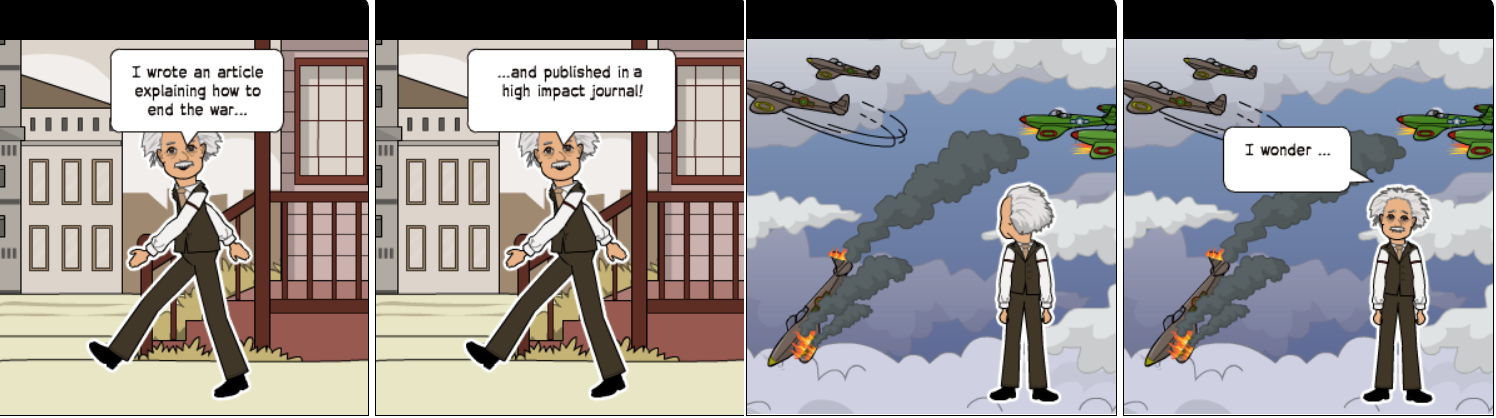

One might wonder why should we co-laborate even better? As one of the scholars noted during a discussion on the question of innovation, „we failed in something. Maybe in explaining. What we do is discussing together how the world works and what who performs, but we fail in communication with people outside academia.“ – „So what should we do?“ asked someone else. Should we engage differently? Or innovate more?

I suggest, we should innovate on our engagements and co-laborations with the world outside academia. For example, Science is entangled with many other world-ings: politics, but also values, cultures, and non-human agencies. At least within the STS epistemic mode, we agree on that. Yet, do we share this, quite innovative, quite revolutionary thought with either specific communities, or even the general public? Is it even possible? How should we innovate our relations with non-academics?

There are no magic answers (certainly not in this short piece of a text). However, if we understood engagement, innovation and knowledge not as final products but as processes, it will make us reflect above asked questions every time, not once but repeatedly, continuously. As much as our co-laborators whose world we study are shaping our research and our findings, we as social researchers are shaping their worlds and their understandings. As social science researchers, we already are part of our „fields“. We do engage in some, more or less explicit, more or less reflected and analyzed, ways. We co-create worlds (or world-ings) we study and shape them back. There are certainly many forms of engagement: sharing and support, teaching and public education, social critique, co-laboration, collaboration, advocacy, activism, to name some of them. Some scholars notice that while doing research, we (at least as ethnographers) tend not to co-laborate with those we do not like. That must have consequences on the disciplines, on the fields of study, and on the relations with others: politicians, economists, broader public. This makes the first point in innovation of the relations between academics and non-academics: to open ourselves to those worlds we marginalize for our lack of sympathy.

The second point should be to think through our communication strategy with non-academics. It took decades after Claude Lorius raised what is now considered to be the first scientific concern about climate change, for the general public, politics, economists, and others to somewhat incorporate it into their ontologies and epistemologies. We should try to learn from this and push the right buttons faster this time. If we want to be part of innovations, not only do we need to accept other reflexivities, but we also need to care about relationships, and to the use of knowledge depending on those relationships – not only before and during the process of research, but especially after the research is done.

We need to find out what is important, how the knowledge is used in practice and whether those we are aiming for and relate to, pick up on what we are saying. To do so, it is not only important to have a thought-through communication strategy (Calhoun 2009). We also need to keep analyzing our own world, our own processes we are living in, and co-laborate with others, including non-academics, on it. Even without magic answers, if we want to innovate, we need to reflect on how to do it, how it has been done by now and what are the limits.

I call for more openness. Let´s open the tower of academia. Let´s take the time and energy to write to the daily newspaper, comment on what is happening – credit academics and junior researchers for their writings, and public events outside academia. Let´s collectively, and openly, talk about changes needed both within and outside academia. Let´s co-laborate with those we do not like (Niewöhner 2016). Let´s institutionalize applied STS. Let´s be creative in methods. And let´s collectively reflect on what we are doing, not only as academics but as part of the broad public. At the end, we will not be alone, in the thinking and doing.